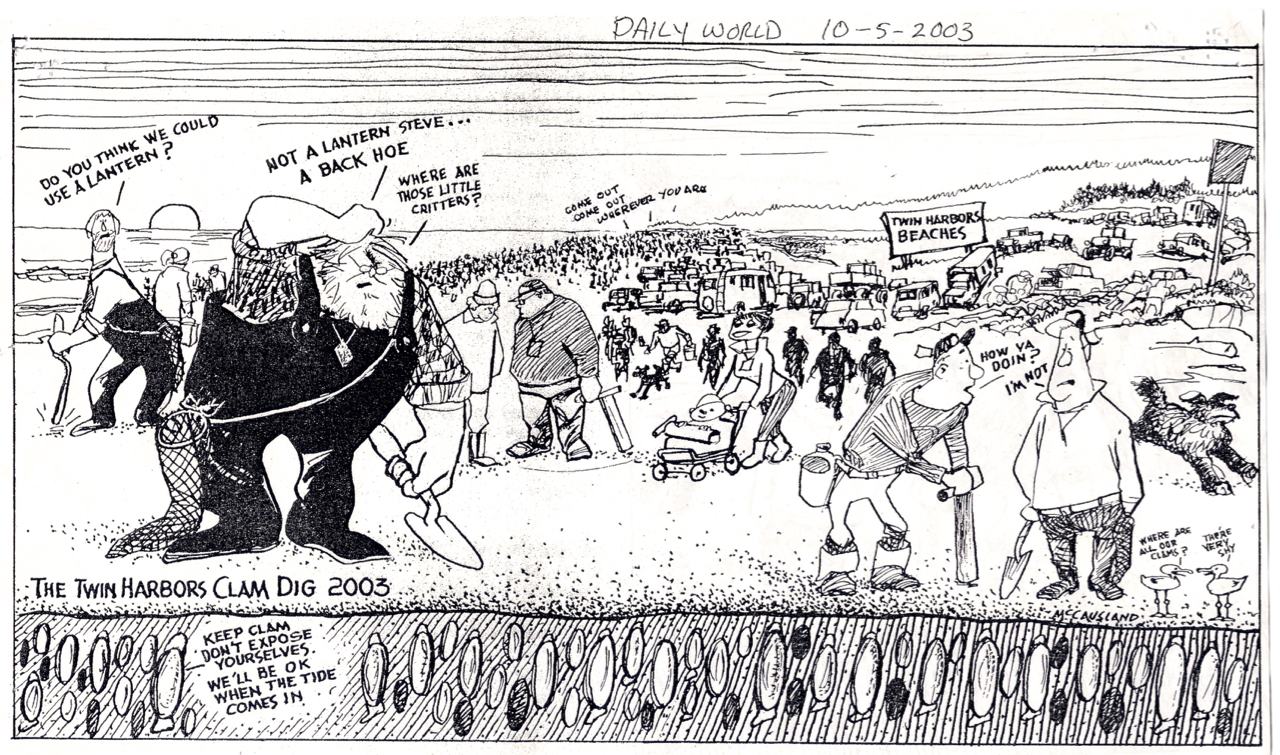

Arriving at the beach in winter in early evening, for a night-time dig

Rich went to a night dig at Copalis in early February, with his friend Mike and Mike’s kid in second grade. It was a Sunday. They arrived about 4 PM for a 6:30 PM low tide. Rich gave this report:

<<We took the Ocean City beach access road, and drove north up the beach several miles. Mike brought a giant pile of wood in the back of his pick-up, split fir, nice and dry, for a fire. The temp was 40 degrees and it was blowing. It was cold. There were other people and cars on the beach, but it wasn’t crowded. Mike had the bright idea we should be put ourselves on Gaia, a GPS tracking app. That way, we could follow the track back to the car. It can be hard to find the car when night falls, in the blackness of the beach. Like being in a cave.

We started digging right away to catch the light; there were a lot of shows, but the clams were small. I was digging with the shovel, prospecting and pounding the sand near the surf. I started looking for bigger shows, to get bigger clams. Mike and his son each had a tube. So there we are, digging and digging and digging. It’s getting colder, and dark. I had my giant headlamp on. Mike’s stopped working. “Hey” he said, “I paid like $19 for that on Amazon.” Mike and his son together have 7 clams. I want to get my limit. I say, “You have the track back to the car. We’re a little south. Maybe go back to the car?” They think this is a good idea.

I ask, “How will I know where you are when I’m done? Can I call you on the phone?”

“The ringer on my phone doesn’t work,” Mike says.

“How will I know where you are?”

“I’ll light a big fire.”

Big fires are distinctive, so that seemed like a good plan. And off they go.

I’m digging, clams are on the deeper side, and it’s cold, but I finally get my limit. The clams at the largest are 4 inches. I start back up the beach, looking for a bonfire. Given the amount of wood Mike brought you should see the fire from space. But I don’t see anything. It’s just black. It’s now late. The beach is desolate. At first there’s a big truck with a blinking light, in what I take to be about the right location. But then that’s gone; they have their limit or whatever and have departed. All that’s left is night and darkness.

I continue walking south, thinking, I’ll see him if I just go in a straight line. I’m uneasy. Where the heck are they? Then I see a tiny spark. Practically a hallucination. I walk in that direction. When I get close I see it’s them. He has started the fire but it’s behind the car. In a pit. I couldn’t see the fire till I was right next to it. I was lucky to find him. I just happened to see some sparks flying up.

“Hey man, the fire is hidden in a pit, behind the car. I had no way of finding you. I just happened on you. What’s the deal?”

“The wind was blowing so much, we had to make this giant pit,” he says.

I warmed up by the fire, and we ate marshmallows, and heated some stew. It’s tough when it’s cold and windy, and dark. And even tougher when your buddy hides the fire in a hole. Always assume the worst with Mike>>

A beach fire is a welcome companion at a night dig

.

.